Two Groups Who Cannot Be Traced Back to an Immigrant Population Are:

By Chair Cecilia Rouse, Lisa Barrow, Kevin Rinz, and Evan Soltas

The United States is often described as a nation of immigrants. With the exception of Native Americans, the vast majority of Americans are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants or enslaved people. This diversity has been celebrated for its contributions to American culture through cuisine, language, and the arts, among many other influences.

Immigrants also make an important contribution to the U.S. economy. Most directly, immigration increases potential economic output by increasing the size of the labor force. Immigrants also contribute to increasing productivity. Economists Gaetano Basso and Giovanni Peri find that immigrants are more mobile than natives in response to local economic conditions, perhaps because they have fewer long-standing familial and community ties, helping labor markets to function more efficiently. Economists Jennifer Hunt and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle have also shown that immigrants boost innovation, a key factor in generating improvements in living standards. Specifically, they find that a 1 percentage point increase in the population share of immigrant college graduates increases patents per capita by 9 percent to 18 percent.

While most immigrants residing in the United States are legally authorized to live and work here, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimates the population of unauthorized immigrants to be roughly 11.4 million as of 2018. This estimate and those used by researchers include beneficiaries of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Temporary Protected Status (TPS), even though both groups have legal authorization to live and work in the United States on a temporary basis.[1] This diverse population also includes other individuals who either entered without passing through immigration (unauthorized entry), or legally came to the United States on a temporary basis and then overstayed their visa.[2] Most of these individuals may not legally work or receive safety-net benefits—or only can under substantial restrictions.

This blog discusses the economics of legalizing unauthorized immigrants. Some critics claim that legalizing unauthorized immigrants, as proposed by the Build Back Better framework, could be costly because they would become eligible for additional social insurance benefits such as Medicaid. However, granting permanent legal status would also likely raise tax revenues, increase productivity, and have additional benefits for the children of these immigrants, generating substantial economic value for the country.

Permanent legal status is likely to increase the effective labor supply of unauthorized immigrants.

About 73 percent of unauthorized-immigrant adults ages 18 to 65 were employed in any given year from 2014 to 2019, roughly equal to the employment rates of non-citizen legal residents and U.S. citizens.[3] Permanent legal status would likely allow these workers to be more productive, generating gains that could be realized through a variety of channels.

Critically, permanent legal status would allow these currently unauthorized immigrants to pursue and accept jobs for which their skills are well-suited, rather than being restricted to particular sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, construction, and leisure and hospitality, where employers often do not insist on legal status and where wages are lower on average. For example, around one-half of workers in the U.S. dairy industry—which in 2018 paid between $11 and $13 an hour for general labor—are immigrants, most of whom are thought to be unauthorized.[4] Without legal status, unauthorized immigrants have limited opportunities for job mobility, a key channel by which other workers find better, more productive employment matches over their careers.

Comparisons between the earnings of authorized and unauthorized immigrants suggest that limited job opportunities cause talent to be misallocated, reducing productivity. Unauthorized-immigrant workers have been estimated to earn about 40 percent less per hour than native-born workers and about 35 percent less per hour than legal immigrants. A large part of these gaps can be explained by differences in average skills as measured by educational attainment; however, after adjusting for these and other demographic differences, this research continues to find a significant "wage penalty" for unauthorized workers ranging from 4 percent to 24 percent of their hourly wage. Further, we estimate that there is no wage penalty for unauthorized-immigrant workers relative to similar legal immigrants within the same occupation and industry, which suggests the penalty arises from being confined to low-paying jobs.[5]

In addition to employment opportunities, evidence from prior legalizations in the United States and in other countries suggests that legalization also encourages immigrants to improve their language skills, induces them to complete additional education and training, and improves their health outcomes, all of which make them more productive members of society. For example, evidence from Germany finds that faster access to citizenship led immigrant women to improve their language skills in addition to increasing their labor force attachment. In a study of U.S. teenagers born to the same immigrant families—but whose legal status varies due to the countries in which they were born—the unauthorized-immigrant teenagers were about 2.6 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in school. In addition, evidence from the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) and DACA shows these reforms increased schooling for previously-unauthorized immigrants. Finally, a recent economic study also suggests that DACA-recipients experienced improved physical and mental health, which contributes to increased productivity.

In a market economy, employees' productivity influences their pay. As a result, productivity improvements—through better job matches, investments in skills, and increases in physical and mental health—should be reflected in increased wages among the legalized immigrants. Indeed, the research evidence supports this hypothesis. For example, research finds that the wages of DACA-eligible Dreamers rose 4 to 5 percent by 2016 relative to those not eligible.[6] Another study concludes that the DACA-related gains in earnings for unauthorized workers were largest among the lowest paid workers. These results signify that even though these unauthorized immigrants may currently be working in the United States, providing them with legal permanent status would increase their effective labor supply, that is, the work their greater productivity enables them to do. Importantly, this increase in productivity is foundational for improving U.S. economic growth.

Given that providing legal status to unauthorized immigrants would increase their effective labor supply, critics of legalization argue there could be adverse labor market consequences for native and other immigrant workers. While there is not a large economics literature on the labor market effects of legalization on other workers, in a well-cited National Academies report on the economic and fiscal impact of immigration, a distinguished group of experts concludes that in the longer run, the effect of immigration on wages overall is very small.[7]

Permanent legal status would likely have implications for costs and revenues for the Federal government.

While granting permanent legal status to unauthorized immigrants would likely boost economic growth, some are concerned about the price tag, given that an increased number of legal immigrants could enroll in, and raise costs of, social benefit programs. However, some of this increased cost would likely be offset by higher tax contributions.[8]

Consider first the potential increase in costs to the Federal government associated with receipt of social benefits. Legal status may make undocumented immigrants more comfortable using Federal benefits for which they are already eligible, such as emergency health services under Medicaid and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). In addition, newly-legalized immigrants could take up social benefits for which they were previously ineligible due to their unauthorized status. Based on benefit use among demographically-similar, non-citizen legal immigrants, this increase in take-up could be significant. For example, many of these immigrants could become fully eligible for Medicaid.[9] Finally, granting legal status could also increase benefit take-up among citizen or authorized-immigrant relatives of undocumented immigrants; several studies find that the threat of an undocumented relative being deported discouraged benefit take-up by citizen members of the same household, even though those citizens are eligible for benefits and cannot be deported.

However, much of the direct fiscal cost of these public benefits is likely to be repaid due to increased tax contributions from the immigrants, and, in the long run, by positive fiscal contributions from their children. Anyone working in the United States is supposed to be paying taxes; however, Federal income tax compliance rates for unauthorized immigrants are unknown. Several government agencies and nongovernmental organizations estimate rates between 50 and 75 percent. By comparison, tax compliance rates on ordinary wage income are close to 100 percent for the U.S. population as a whole, according to the U.S. Treasury Department.

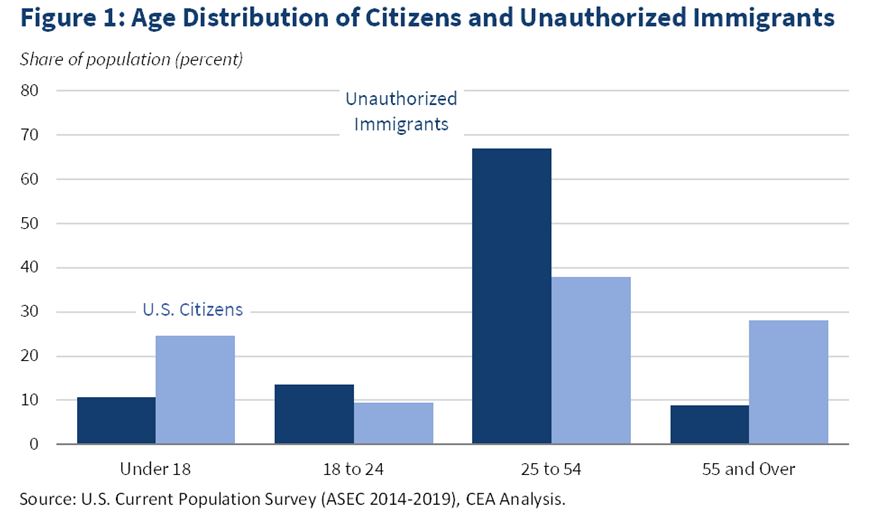

Shifts from the informal to the formal sector that are expected to result from legal status would likely increase tax compliance rates. Indeed, after the passage of IRCA, researchers found that income tax compliance rates of previously-unauthorized immigrants in California became comparable to other residents. Combined with the wage gains, gross tax revenues would increase. Moreover, undocumented immigrants are disproportionately of prime-working age (see Figure 1) and relatively younger than prime-age U.S. citizens. Therefore, they are likely to have many working years during which they will be paying these higher payroll and income taxes if they are legalized.

Finally, many children of unauthorized immigrants grow up in households below the Federal poverty level because their parents cannot secure higher-paying work due to their immigration status. Growing up poor can be harmful for child development, and providing public health insurance and nutrition assistance has been shown to improve the health of immigrant children. In general, the direct fiscal cost of public assistance for low-income children is thought to be substantially or fully offset in the long run. The costs are offset by increases in tax revenues and reductions in spending on government programs when these children grow up to become higher-earning adults than they would have had they not received assistance.[10]

Conclusion

Immigrants have made innumerable contributions to American business and society. However, current law confines millions of them to a life in the shadows, without the rights to be fully economically engaged or have access to foundational social protections. Such treatment inflicts harms on unauthorized immigrants themselves and their families—many of which include U.S. citizens and non-citizen legal residents—as well as to the broader economy.

Though some argue that increased take-up of social programs would generate a substantial fiscal cost to the government, the productivity of the newly-legalized would likely increase, which would benefit all in the United States by expanding economic output. Further, the ensuing increase in wages and compliance with tax requirements would increase their contributions to public sector finances, and their children would benefit as well. Allowing currently unauthorized workers to engage fully in the labor force would not only benefit the immigrants and their families, but society as a whole.

[1] DHS estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population are calculated as the residual from subtracting the legally-resident, foreign-born population from the total foreign-born population. Dreamers (individuals born between 1981 and 2012 brought to the United States as children) who applied to and were accepted into the DACA program can legally work and reside in the United States, but only for two years, at which point they must apply to renew their status; the Supreme Court ruled in June 2020 that the Trump Administration could not end the program, but the U.S. District Court in Southern Texas ruled in July 2021 that the program is not lawful. While those currently in the DACA program are still protected and can reapply, new applicants are not accepted, and the case is making its way through the Federal courts. TPS is granted only until resolution of the conditions in a recipient's country of origin that make it difficult or unsafe to return.

[2] Unauthorized immigrants do not include people who have been granted asylum or refugee status or nonimmigrant residents, such as students and temporary workers, who have been granted permission to study or work in the United States for a limited period of time and for a specific purpose.

[3] CEA analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from 2014 to 2019.

[4] The average hourly wage in the United States in 2020 was about $27 an hour.

[5] Based on CEA analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from 2014 to 2019.

[6] Evidence from the wage impacts of naturalization in the United States and other countries; smaller extensions of work authorization to particular groups of unauthorized immigrants, such as those aided by the Chinese Student Protection Act of 1992; and reforms that have restricted employment options for unauthorized workers, also suggest that granting legal status would improve labor market outcomes of unauthorized workers.

[7] See also David Card's Richard T. Ely Lecture to the American Economic Association in which he argues that immigrants have had at most small impacts on wage inequality among natives.

[8] We note that the fiscal impacts of providing legal permanent status to existing unauthorized immigrants likely differ from prior analyses of the fiscal impacts of immigration generally, as unauthorized immigrants are already in the country, and many currently work, pay taxes, and receive some forms of government benefits. This existing relationship with the government makes it necessary to estimate how their rates of tax compliance and take-up of benefits would change if they gained legal status. Such calculations are not straightforward and require important assumptions, some with scarce relevant data and evidence that could inform them.

[9] Unauthorized immigrants who entered the United States after August 22, 1996—the date Federal welfare reforms were signed into law—would generally be eligible only after a waiting period of five years of legal residence for several benefits, including non-emergency health services under Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

[10] At present the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) does not account for any long-run fiscal return to public benefit programs, suggesting that current approaches to "scoring" the fiscal impacts of legal status are likely to overstate their true fiscal cost.

Two Groups Who Cannot Be Traced Back to an Immigrant Population Are:

Source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/09/17/the-economic-benefits-of-extending-permanent-legal-status-to-unauthorized-immigrants/

0 Response to "Two Groups Who Cannot Be Traced Back to an Immigrant Population Are:"

إرسال تعليق